The Chitari Foundation: A Best of All Worlds Approach to Healthcare

The Chitari Foundation envisions establishing hospitals and clinics that will provide inpatient and outpatient services, as well as medical research and education. These centers will provide a foundation where all medical modalities collaborate to promote health in people, communities, and, ultimately, the global environment.

My mom died in a car accident when I was 23 years old. She was in terrible pain from a couple of other accidents. I had given her several books on healing, acupuncture, hypnosis, and healthy food, anything I could find. Yet, the imbalance of the stupefying drugs she was given by allopathic physicians (in what I came to realize amounted to overkill) killed her instead of curing her. I remember asking: “What if we approached medicine differently?”

After years of studying premedicine, biochemistry, psychology, and environmental medicine, I decided to go to acupuncture school in Boston, Massachusetts. I studied with several innovative teachers, and as an acupuncturist I helped start the Pain and Stress Clinic at Lemuel Shattuck Hospital, in central Boston. There, I experienced a different paradigm of medicine. Practitioners of various sorts were collaborating on difficult and extreme patients. The results were astounding! How I wished my mother could have been among them.

A Solution to the Problem? Collaboration

A Solution to the Problem? Collaboration

In the early 1980s, I was invited to cofound the Oregon College of Oriental Medicine within the National College of Natural Medicine, in Portland. Oregon College of Oriental Medicine has become one of the top Oriental Medicine schools in the country. Coincidentally, I discovered that the National College of Natural Medicine’s ND degree was the type of program in which I had always wanted to study. The ND program integrated all that was relevant in an allopathic medical school with ideas of natural medicine. I drank in the course work with the thirst of someone dying in the desert.

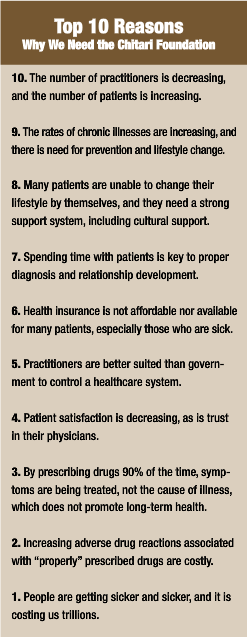

My quest became centered on the question “Why are we so sick, and what can we do about it?” With experience, the answer is emerging. Our culture is experiencing unprecedented challenges. There is dysfunction due to toxins, new pathogens, poor diet, and stress. Similarly, there is a lack of what keeps us well, including community, hope, love, and an integrated healthcare system that acknowledges, explores, and uses the multitude of modalities available to those in need. So many life essentials are out of balance. Our health reflects this imbalance.

Having encountered the many aspects that full health requires, I realized that physicians cannot correct the imbalance alone in our individual practices. It is essential for us to work together. We need all the great teachers and all the great physicians to focus with patients and their communities on healing. Only then will we find the causes of the illnesses and be able to change them.

Business Case for Collaborative Healthcare

The need for a collaborative solution has never been greater. The current health reform law calls for increased access to care for more than 30 million people, but we are 17 000 primary care physicians short.1 By 2025, we will have a deficit of 124 000 primary care practitioners.2 One solution to the problem is to find a way to create a healthier population, despite a shortage of practitioners. Another solution is to use all available primary care practitioners with greater efficiency by working together to deliver great healthcare. It is clear that a combination of both options will be necessary.

By 2030, because of the aging of the baby boomers, there will be twice as many people as today who are older than 65 years.3 Current health trends forecast the following statistics: 33% will be obese, 25% will have diabetes, and 50% will have arthritis.3 There will be an 800% increase in knee replacements.4

In 2003, there was an additional loss of more than $1 billion from illnesses due to chronic disease and secondary health problems.5 Statistics for 2010 show that this loss increased from $1 billion to more than $1 trillion!6

Another benchmark of the need for a new approach to healthcare is what practitioners call adverse drug reactions. Even with correct prescription use, drug adverse effects occur and may be potentially dangerous, even fatal. In 1997, the cost of adverse drug reactions was estimated to be $1.63 to remediate every $1.00 spent incorrectly on drugs “properly” prescribed according to guidelines.7 Individual variations in processing drugs are not being understood or considered. We need to personalize care and improve health, reducing the need for drugs.7-9

People are also getting sicker for more days per year, the cost of which is much suffering and great financial expense.10 There are tremendous increases in many expensive illnesses like diabetes, cancer, and heart disease. Many individuals cannot afford healthcare or medical insurance, so illnesses are not treated until they are catastrophic and very expensive.

Facing this cost crisis, we cannot afford not to make a change. Our mothers and fathers, our sisters and brothers, and our children and communities need better access to improved healthcare that is affordable, effective, and preventive and carries fewer risks.

Medical Case for Collaborative Healthcare

Naturopathic medicine can have a central role in fixing our current healthcare problems. Today, new MDs are increasingly choosing to do a residency that incorporates naturopathic programs. Allopathic residencies are experiencing a lack of applicants.11

A 7-year preliminary study12 among 70 000 individuals in Illinois found that the use of chiropractors and primary care physicians oriented toward natural medicine before allopathic physicians reduced costs dramatically. The study reported that the first-line use of naturopathic medicine had the following results:

- Reduced pharmacy costs by 85%

- Reduced hospital admissions by 60.2%

- Reduced hospital days by 59%

- Reduced outpatient services and procedures by 62%

Although this integrative medicine investigation in Illinois was a preliminary study, not a fully developed program, it had outstanding results.

Quite simply, we are getting fatter and sicker, and this means fewer productive workdays and higher healthcare costs. Naturopathic medicine reduces employee healthcare costs significantly in institutions tracking such programs.13 Patient satisfaction is much higher with naturopathic providers. In turn, this leads to improved reimbursement rates for patients and providers from insurance carriers. Member satisfaction surveys are consistently higher for naturopathic practitioners. Hospitals using naturopathic medicine are doing better financially, with greater patient satisfaction.

Expenditures for illnesses like diabetes, asthma, obesity, and cardiovascular disease are going to increase. These illnesses can be greatly mitigated by the inclusion of naturopathic medicine in healthcare.14,15

Kicking the can down the road is no longer viable. In other words, just treating the symptoms is dysfunctional. The incidence of heart disease, cancer, diabetes, infections, and other disorders can be reduced by preventive and holistic medicine,16 engendering patient satisfaction and dramatically reducing the personal and social financial burdens.

What We Propose

To put the world in order, we must put the nation in order. To put the nation in order, we must put the family in order. To put the family in order, we must cultivate our personal life. To cultivate our personal life, we must make our ‘hearts’ right.

Confucius (551-479 bc)

When the environment is creating the illness, then we need to treat the environment and the illness to effect complete care. The Chitari Foundation was conceived by me and a wonderful anthropologist from Nepal, Dr Pramod Parajuli. We spent 2 years designing a new system of healing with worldwide application. Then, 3 amazing individuals helped me further develop the program, including social worker Jeanette Chardon, MSW; nun and natural MD student Bonnie Skakel, ND; and teacher and counselor Carla Austin. In 2008, the Chitari Foundation was officially established with nonprofit status. Soon, many other people contributed and poured their hearts into our vision to foster a healthier world.

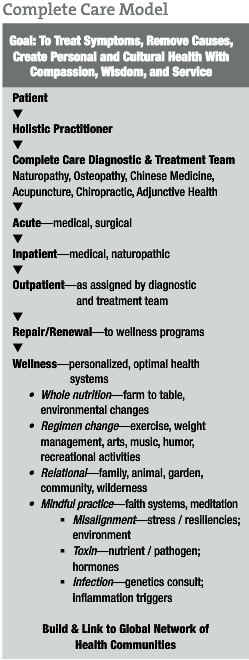

Chitari in Nepalese means meeting place. The Chitari Foundation aims to create hospitals and clinics that will provide inpatient and outpatient services, plus research and education, where all medicines collaborate to promote health in people, their communities, and, ultimately, the global environment. We will treat the causes of illness too.

The Chitari Foundation (www.Chitari.org) is a nonprofit organization created to deliver a healthcare system that will optimize health, not only through personalized medicine for the individual but also by creating cultural health. Our mission is to provide innovative healthcare through education, research centers, and a hospital with clinics that integrate medicine to benefit the total health and sustainability of our global community. We will also support and be supported by sustainable organic and kitchen gardens and a farmers market to provide our green facility with clean whole food, a must for nurturing basic health.

We foresee integrative clinics for patient care with affordable Traditional Chinese, natural, chiropractic, and allopathic medicine to transform patients’ physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual well-being. A Chitari Foundation center will offer many levels of care, including skilled nursing facilities, hospitals with research, and multidisciplinary education centers for doctoral training and education, plus promotion of community education and wellness. Our model provides complete and effective care, across all modalities, allowing affordable humane healthcare for all.

Professionals of all disciplines will work together to create an affordable, collaborative, and sustainable medical model. Our plan is to bring together allopathic and natural medicine practitioners to form the first nationally recognized training ground in collaborative medicine.

The board of directors of the Chitari Foundation is raising funds and is searching for our initial clinic site in the Portland area. We foresee that the model will germinate other sites throughout the United States and, eventually, worldwide.

The Chitari Foundation may be among the first of its kind, but by putting our hearts right, it will not be the only meeting place to bring together the best of all worlds and to solve these issues. Imagine the brilliance of all medicines collaborating to restore the health in people, their communities, and, ultimately, the global environment. We would nurture collaboration with any other like institutions. As my mom often told me, “The mission may be hard, but never impossible.”

How Would It Work?

A patient would come to us and be seen by a health advocate. This health coach would assess (triage) the patient and will recommend that he or she should see certain practitioners.

For low back pain, the patient might see a chiropractor, acupuncturist, orthopedist, and massage therapist. If not better after a specified time, the patient might be worked up by a rheumatologist or other appropriate physician.

A patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis would perhaps see a neurologist, infectious disease specialist, acupuncturist, or chiropractor. He or she would participate in a qi gong class, have nutritional status testing, receive toxicology and gene evaluations, and undergo whatever else the health team advises to diagnose and resolve underlying causes of disease. An exemplary case study is presented herein.

For a patient participating in a “wellness naturally program,” various tests could be performed, such as genetics, hormone profile, gastrointestinal evaluation, neurological health, and lifestyle assessment. Some patients would come and stay at the center to work on changes in lifestyle, through class participation, to restore health. Tiers in patient care would be developed to help patients find the level of care needed for their optional care, such as outpatient, inpatient, and lifestyle classes. They would learn life skills needed to be optimally healthy. The medical teams would meet regularly and devise a combination of approaches using allopathic and natural medicine, working together with patients to obtain the best outcomes. During meetings of the health teams, practitioners would then reassess and modify therapies if necessary to help their patients. All therapies would be added to the data in the research department, and effective therapies would be published and promoted in future protocols. Patients, and possibly their families, would partake in this process and be as much a part of a healthy strategies development team as they cared to be. All patients and staff would receive training and have access to delightful healthy meals, classes on stress reduction, wellness programs, and any needed curricula or classes for their health.

Case Study

A sample application of this program is exemplified by a patient who came to see me 8 years ago. He was diagnosed as having amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and was given a short time to live. He was having trouble ambulating, thinking, and breathing. His neurologist had told him to “get your things in order.” At his first visit to me, I assessed his situation. He had signs of malabsorption in his blood workup. He was a housepainter and a world traveler, to Thailand, India, and South America. He had also lived on the East Coast, in Vermont, Maine, and Massachusetts.

His laboratory test results showed the following:

- He was positive for high lead and mercury levels.

- He showed significant lack of many nutrients, including vitamin B12.

- He was positive for a tapeworm and ameba.

- He was high positive for Lyme disease.

- He also tested positive for gluten allergy.

His treatment consisted of treating the tapeworm and ameba with albendazole and a parasite formula. Then, I prescribed Uncaria tomentosa and enzymes for the Lyme disease. Acupuncture was performed to stimulate his nervous system back online. We introduced an anti-inflammatory diet, eliminating gluten. We gave him nutrients that were necessary for his body to heal, including B vitamins, acetyl-l-carnitine, Hericium erinaceus, and omega-3 fatty acids. We then performed dimercaptosuccinic acid oral chelation for the mercury and lead. He practiced qi gong and tai qi and included laugh therapy. He knew he was getting better, and that helped. The patient also fell in love as he healed (one of the greatest healers). He was better after 6 months and was symptom free at 12 months, with occasional flare-up of symptoms. At 18 months, his symptoms were gone. He sends me a Christmas card each year and comes in to treat an occasional injury.

Was amyotrophic lateral sclerosis misdiagnosed in this patient, or did a series of unfortunate events cause neural inflammation and decline because of his particular genetic makeup? Could this combination of events always be reversible and be applicable to other diseases? These are the types of questions we would expect to answer at the Chitari Foundation centers.

References:

- Sataline S, Wang SS. Medical schools can’t keep up: as ranks of insured expand, nation faces shortage of 150,000 doctors in 15 years. WSJ.com. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304506904575180331528424238.html. Accessed January 25, 2012.

- Kirch DG. President’s address: the new excellence. Presented at: 122nd Annual Meeting of the Association of American Medical Colleges; November 6, 2011; Denver, CO.

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey: the principal source of information on the health of the U.S. population. June 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/brochure2007june.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2010.

- Sanmartin C, McGrail K, Dunbar M, Bohm E. Using population data to measure outcomes of care: the case of hip and knee replacements. Health Rep. 2010;21(2):23-30.

- Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56(10):1-120.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic diseases and health promotion. July 7, 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/overview.htm. Accessed January 14, 2012.

- Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279(15):1200-1205.

- Goulding MR. Inappropriate medication prescribing for elderly ambulatory care patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:305-312.

- Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1997;277(4):307-311.

- Doyle R. Getting sicker: state budget constraints threaten public health. Sci Am. 2004;291(5):30.

- RAND Health. Complementary and alternative medicine. http://www.rand.org/health/browse-health/complementary-and-alternative-medicine.1.html. Accessed January 20, 2012.

- Sarnat RL, Winterstein J, Cambron JA. Clinical utilization and cost outcomes from an integrative medicine independent physician association: an additional 3-year update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(4):263-269.

- Klinger B. Core competencies in integrative medicine for medical school curricula: a proposal. Acad Med. 2004;79(6):521-531.

- Loeppke R. The value of health and the power of prevention. Int J Workplace Health Manage. 2008;1(2):95-108. doi:10.1108/17538350810893892.

- Devol R, Bedroussian A, Charuworn A, et al. An Unhealthy America: The Economic Burden of Chronic Disease: Charting a New Course to Save Lives and Increase Productivity and Economic Growth. Santa Monica, CA: Milken Institute; 2007.

- Williamson DF, Vinicor F, Bowman BA; Centers For Disease Control And Prevention Primary Prevention Working Group. Primary prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by lifestyle intervention: implications for health policy. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(11):951-957.

This article was originally published by Naturopathic Doctor News & Review.

A Solution to the Problem? Collaboration

A Solution to the Problem? Collaboration